CONTESTED REMEMBRANCE

Legal and Political Challenges in Acknowledging

the Holodomor

MATILDA MOLODYNSKI STOKES

In Ukraine, memory is political. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the ongoing debate over the recognition of the Holodomor as genocide. Nearly a century later, the famine of 1932–33 remains a highly contested subject, both within Ukraine and internationally. The legal and political interpretation of the Holodomor has always been conducted under the influence of past or present russian aggression, whether during the early 2000s, when the first memorial was established, or in the present day.

Whether in the context of recognition of the genocidal nature of the Holodomor by the EU or the refusal of its recognition by the UN, the debate surrounding the legal categorisation of the Holodomor under the Genocide Convention has stood under the shadow of russian dominance over international political, legal and academic spheres.

I first came across the Holodomor during my studies at the University of Warsaw. After enrolling on a course that promised to guide us through the complex field of both historical and contemporary Ukrainian politics, I logged on every week to a lecture delivered by a fantastic professor who, while teaching from Kyiv, had taken up a temporary position in Poland due to the invasion. As we were taken through Ukraine’s long history of erasure and subjugation by its neighbours — and, most importantly, due to the professor’s insistence on highlighting this point — I began to realise the parallels between historical injustice and russia’s war in Ukraine today. It is because of historical and contemporary efforts to minimise and suppress the Ukrainian language, culture and national identity that the writing of Ukraine’s history is vital in ensuring these aims of erasure do not succeed. I therefore hope to make a small contribution to this effort here, with a discussion of how denial has functioned as a barrier to the recognition of the Holodomor as an act of genocide.

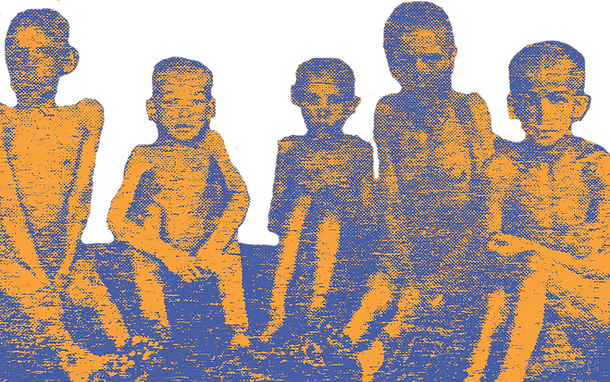

The key aspect of the Holodomor period (1932–1933) that sets it apart from the earlier (1921–1923) and later (1946–1947) famines is its artificial and intentional nature. Marc Jansen (2017), among others, addresses this in his scholarship, asserting that although many claim that poor harvests and weather conditions played a role in the famine, the primary cause was ‘chaos following the forced collectivisation of agriculture,’ a policy implemented by the Soviet regime. Moscow had rejected requests from Ukrainian officials to reduce grain quotas and instead pursued a policy of searching Ukrainian collectivised farms, confiscating any last ‘hidden’ remnants of grain that had been kept for survival (Jansen, 2017). The level of starvation reached by May 1933, the time when ‘little help’ had arrived, had driven people to desperation (Jansen, 2017).

There are those scholars and those within the political field who reject the categorisation of the Holodomor as a genocide. Often, this view is held by those within the modern russian political sphere. This piece will primarily focus on examples of the denial of the event’s genocidal character within the international legal sphere. To thoroughly discuss the role the Soviet government played in exacerbating the famine and the extent to which its intent can be proven, we must analyse the context in which the Holodomor famine occurred. Mark Von Hagen (2013) asserts that during the 1910s in Ukraine numerous instances of violence had occurred against Ukrainian intellectuals, that russian military forces would often persecute those who were heard speaking the Ukrainian language, and that a policy of annihilation of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, including the abolition of Ukrainian

language education, had been pursued in the

region. This demonstrates a similar policy of

eliminating specific groups within Ukrainian

society. Additionally, Von Hagen (2016) analyses

the policy of forced collectivisation, and the

‘famines that accompanied it,’ in terms of its links

with the rise of the NKVD and the Gulag,

linking Holodomor and other tools of

violent oppression.

The intention of the Soviet authorities regarding the Holodomor has been identified by many scholars as being to finally ‘crush the peasants’ resistance’ to collectivisation (Khiterer, 2020). In 1930, approximately 6,000 peasant revolts occurred in the Soviet Union, with nearly 2,000 of these taking place in Ukraine (Khiterer, 2020). It is due to this, and the later policies of confiscation and refusal of aid to certain Ukrainian regions, that led scholars to conclude that the famine was a targeted event against Ukrainian peasants. The Soviet authorities were intent on isolating and containing famine within Ukraine, such as with Stalin personally drafting a letter demanding the closure of borders to prevent victims of starvation from entering more prosperous regions in 1933 (Kulchytsky, 2012). It is clear from this that ethnicity and nationality, based on the frequency of dissent, were the criteria against which the Soviet authorities determined the extent of aid distribution.

The international political and academic reaction to the proposition of the Holodomor as a genocide was of a similar controversial nature to that within the Ukrainian context. The United Nations’ definition of genocide is based primarily on Raphael Lemkin’s working definition, which links mass killing and cultural genocide. Norman Naimark (2015) places a particular focus on Soviet dissent to Lemkin’s definition, as well as their rejection of the inclusion of ‘social and political groups’ within the definition. The inclusion of these two types of groups is crucial for classifying the Holodomor under this definition. Ultimately, due to this dissent, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, adopted in 1948, defined genocide as ‘acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group’, lacking mention of social, political and national groups (Naimark, 2015). Naimark (2015) analyses the further impact that Soviet international influence had on Lemkin’s quest for recognition of the Holodomor within the genocide convention, as his 1953 speech on the subject, ‘Soviet Genocide and Ukraine’, was dismissed mainly due to his ‘extreme anti-Soviet and anti-Communist rhetoric’. Due to the adoption of this version of the genocide convention, the Holodomor continues to not be recognised by the United Nations as a ‘tragedy’, a ‘horror’, an ‘atrocity’, as a ‘tragic page in global history’, but is not deemed as falling under the scope of the genocide convention (Holodomor Museum Kyiv, 2023).

The international political and academic reaction to the proposition of the Holodomor as a genocide was of a similar controversial nature to that within the Ukrainian context. The United Nations’ definition of genocide is based primarily on Raphael Lemkin’s working definition, which links mass killing and cultural genocide. Norman Naimark (2015) places a particular focus on Soviet dissent to Lemkin’s definition, as well as their rejection of the inclusion of ‘social and political groups’ within the definition. The inclusion of these two types of groups is crucial for classifying the Holodomor under this definition. Ultimately, due to this dissent, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, adopted in 1948, defined genocide as ‘acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group’, lacking mention of social, political and national groups (Naimark, 2015). Naimark (2015) analyses the further impact that Soviet international influence had on Lemkin’s quest for recognition of the Holodomor within the genocide convention, as his 1953 speech on the subject, ‘Soviet Genocide and Ukraine’, was dismissed mainly due to his ‘extreme anti-Soviet and anti-Communist rhetoric’. Due to the adoption of this version of the genocide convention, the Holodomor continues to not be recognised by the United Nations as a ‘tragedy’, a ‘horror’, an ‘atrocity’, as a ‘tragic page in global history’, but is not deemed as falling under the scope of the genocide convention (Holodomor Museum Kyiv, 2023).

Recognition of the genocidal nature of the Holodomor by Ukrainian political actors preceded international recognition of the severity of the event. In her scholarship, Tatiana Zhurzhenko (2014) describes the year 2006, in which the Ukrainian parliament passed the ‘Law on the Holodomor of 1932–33 in Ukraine’, declaring the Holodomor as an act of genocide against Ukrainian civilians. The move was opposed by the Party of Regions, which proposed to replace the word ‘genocide’ with ‘crime against humanity,’ and the Communist Party, which denied that the famine was artificially created (Zhurzhenko, 2014). To curb dissent to the classification by the government as a genocide, Yushchenko, in 2007, proposed a new law criminalising the ‘denial of the Holodomor as a Genocide’, although the law was not supported by parliament (Zhurzhenko, 2014).

In November 2008, a national monument to the victims of the Holodomor, known as the ‘Candle of Memory,’ was unveiled in Kyiv as part of an official commemoration of the Holodomor’s 75th anniversary. This ceremony included the establishment of The Memorial in Commemoration of Famine Victims in Ukraine, which, as its name suggests, did not commit to naming the Holodomor as a genocide (Zhurzhenko, 2014). In 2019, the museum was renamed the National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide in recognition of its genocidal nature (Holodomor Museum Kyiv, 2023). Although this form of memorial was successful in Kyiv, a ‘major conflict’ between the regional administration and the mayor emerged in 2007 regarding the memorialisation of victims in the Kharkiv region (Zhurzhenko, 2014). There were disagreements in the Kharkiv regional assembly regarding the memorial, with the most significant obstacle being that the majority of the assembly (aligned with the Party of Regions) officially rejected the definition of the Holodomor as a genocide (Zhurzhenko, 2014).

Works Cited

Jansen, Marc. 2017. “Was the famine in Ukraine genocide?”. RAAM, https://raamoprusland.nl/dossiers/geschiedenis/783_was_de_hongersnood_in_oekraine_genocide.

Khiterer, Victoria. 2020. “The Holodomor and Jews in Kyiv and Ukraine: An Introduction and Observations on a Neglected Topic.” Nationalities Papers 48, no. 3.

Kulchytskyi, Stanislav V. 2012. Holodomor in Ukraine 1932–1933: An Interpretation of Facts. In Holodomor and Gorta Mór: Histories, Memories and Representations of Famine in Ukraine and Ireland, eds. Christian Noack, Lindsay Janssen, and Vincent Comerford. Anthem Series on Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (Anthem Press, 2012).

Naimark, Norman. 2015. “How the Holodomor Can Be Integrated into Our Understanding of Genocide.” East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies, 2015.

Von Hagen, Mark. 2013. “Rethinking the Meaning of the Holodomor: ‘Notes and Materials’ toward a(n) (anti) (post) colonial history of Ukraine.” Taking Measure of the Holodomor (New York: The Center for U.S.-Ukrainian Relations, 2013).

Von Hagen, Mark. 2016. “Wartime Occupation and Peacetime Alien Rule: ‘Notes and Materials’ toward a(n) (anti-) (post-) Colonial History of Ukraine.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 34, no. 1–4: 2015–2016.

Zhurzhenko, Tatiana. 2014. “Commemorating the Famine as Genocide: The Contested Meanings of Holodomor Memorials in Ukraine.” In Memories in Times of Transition, eds. Susanne Buckley-Zistel and Stefanie Schaefer. Series on Transitional Justice (Intersentia, 2014).

Holodomor Museum Kyiv. https://holodomormuseum.org.ua/en/history-of-national-holodomor-genocide-museum/